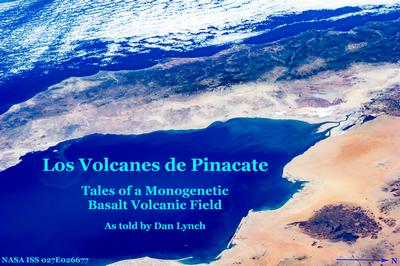

Black Pinacate basalt stands out in sharp contrast to the reddish-tan sand of Gran Desierto de Altar at the northern end of Mar de Cortez - the Gulf of California. Seven-odd million years ago, the northwestward drifting Pacific Plate tore Baja California away from North America, opening the Gulf basin along a new plate boundary between Baja and the Sonoran Desert that is hidden beneath sand and water on the Baja side of the Gulf. Plate tectonic processes are a convenient excuse for basalt volcanism in Pinacate, but the boundary is about 100 km distant from, and more than four million years older than, Pinacate whose heat source seems to have been unaffected.

Opening the Gulf brought the sea inland, and the new base level changed the energy balances of all the rivers emptying into it. The Colorado River somehow integrated itself across the Colorado Plateau from the Rocky Mountains to connect with the newly opening Gulf by about five and a half million years ago. Redbed mudstone from the Colorado Plateau gives the Gran Desierto its warm, reddish color.

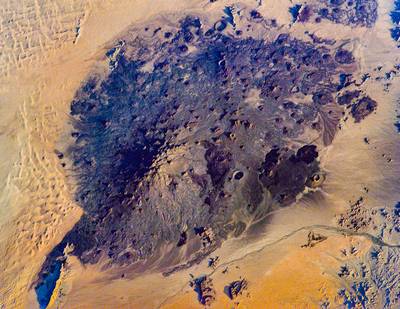

The elements of Pinacate geology are sharply illuminated by the rising sun in this 2003 grab shot from the International Space Station. Hundreds of cinder cone volcanoes and lava flows are scattered across a distinctive gray landscape of their own creation. These Pinacate basalts, draped across a nearly contemporaneous volcanic mountain, cover 1800 km2 of Lower Sonoran Desert.

These small volcanoes are called monogenetic because each was built in one continuous, short eruption - weeks to months, years at most - with thousands of years between eruptions. Volcan Santa Clara, the mountain, is profoundly different; created by numerous eruptions over more than a million years, from the same, evolving magma body.

Pinacate is famous for its giant maar-calderas, those exceptionally large craters clearly visible in a line down the center of the image. Gray crystalline rock mountains of the Basin & Range Geologic Province project through the sand all around the field, proof that the volcanoes are on continental crust. (12/01)

Volcan Santa Clara

Volcan Santa Clara, the most prominent feature in the space image, is a trachyte shield volcano whose official geographic name is “Sierra del Pinacate;” it has two names for historical reasons and because we have learned a lot in the past 50 years. Towering a thousand meters over the desert and visible for hundreds of km, it is a “Cerro” (single mountain) rather than “Sierra” as it is labeled on maps, probably because Pinacate cones make multiple summits on the skyline look like a mountain range. Although Santa Clara’s volume is 60 to 75 km3 (as compared to the <quarter km3 volume of the largest “cinder cone” volcano), it managed to avoid attracting attention during the early explorations of the field.

Santa Clara’s rocks are subordinate, they only peek out in a few places from beneath the Pinacate basalts; small areas of light gray rock can be seen at the base of Pinacate Peak (top center) and in the middle left, with more extensive areas of reddish gray rock on the middle right. These rocks are trachytes, rich in feldspar, whose magmas evolved from a basaltic parent as crystals of dark minerals grew in the liquid and removed the elements that make basalt black. Santa Clara was built by sequential eruptions from a single magma body as it cooled and evolved.

How did Santa Clara become Pinacate and then Santa Clara, again?

The indigenous Ha Ced O’odham probably knew of it as Shuk To’ak (Black mountain, one of many), but no records exist. Fr. Eusebio Fransisco Kino, first European explorer and documenter of Pimeria Alta in the late 1600s, named the mountain “Santa Clara” on his final trek to its summit in 1701 and put this name on his description of the area (others made the maps). Over the next 150 years, Santa Clara was the name of the mountain at the head of the Gulf on dozens of increasingly detailed maps - all safely archived in big city libraries.

Mexican people who had moved into a desert of mostly gray-toned mountains, had no knowledge of Kino or these maps so they related the black mountain to the ubiquitous black Eleodes armata beetle which is called Pinacat’l in the Nahuat’l language of pre-Hispanic Mexico.

Americans in the 1850s, who were mapping the Gadsden Purchase and marking its borders, got this local name for their maps, possibly hearing Pinacat’l as “Pinacate.” Herman Ehrenberg’s 1854 Map of the Gadsden Purchase shows the name “Pinecate Mt” (sic), its first appearance in print.

Kino’s “Santa Clara” was resurrected as a geologic name when it was discovered that the trachyte shield volcano is neither “To’ak” (black) nor is it “Pinacate” (alkali basalt), but something quite different. The official geography remains unchanged. (12/15)

Monogenetic Volcanoes

“Cinder cone” is the common name for monogenetic volcanoes like these more-or-less conical hills on the Santa Clara summit platform. They were built by the energy of volatile constituents of the basalt magma (water, SO2, CO2) boiling out in the topmost conduit. Expanding bubbles blew the liquid into fountains of fire-fragments we call “pyroclasts.” Each blob of liquid was full of bubbles that continued to expand until it was no longer liquid and became “scoria.” The blobs arced radially outward to fall in rings, forming the cone-in-cone (crater-in-cone) hills in the picture.

All of them are scoria cones but only Carnegie (in the right distance) is a true cinder cone. Cinder is super-scoria, basalt froth made of tiny bubbles in vast profusion that stretched the liquid into thin sheets and rods between them as they expanded the liquid a hundred times. Carnegie’s cinder jet blew a blanket over the the top of Santa Clara that covers everything in this photograph. (11/11)

Carnegie, seen from the other side, is located on the north edge of the Santa Clara summit platform. Cinder covers some of the flow basalts, particularly in the lower part of the photo and the northern wall of the cone collapsed down the north flank of Santa Clara in a debris flow, only to be partially rebuilt by the continuing eruption. After the cinder cone building phase, basalt continued to flow from a N70W fissure at the left base of the cone wall; extending 15 km down the east flank of Santa Clara and onto the desert flat as the longest flow in the field.

Cinder is the main economic product of fields like Pinacate, few of those 50 other fields have escaped the scars of prospecting or mining. The cinder mine at La Laja is the largest in Pinacate; but many cinder prospects scar other parts of the field. It was opened in the 1960s to provide material for building Highway 2 that was planned to cross northern Mexico. After the part across Sonora was finished, cinder was shipped to Phoenix for landscaping until the mine closed in 1978. This mine, only 6 km from the highway, saved Tecolote from destruction.

La Silla (the chair), near Highway 2 on the west, represents the typical Pinacate monogenetic volcano (465 have been mapped). It is a hill of basalt scoria slowly melting away in the desert’s violent but very sporadic rainstorms. Both spectacular and isolated, it is one of three Pinacate volcanoes perched on crystalline rocks of basin & range mountains..

Young cones, like Julian Hayden, the black one in this group of three, have sharp cone edges and no slope erosion. Hayden erupted onto the north side of a larger, older cone that shows rills down its slopes and rounder crater edges. This cone, in turn, had erupted adjacent to an even older cone whose crater has been eroded into an open “U.” The Hayden lava flow in the foreground came out on the high point of the underlying slope so it split into branches, east and west around the Hayden group. (11/11)

The smallest intact Pinacate volcano is Volcancito Coyote, a N60W, 280-meter-long fissure, decorated by a dozen or so little conelets, barely visible along the left side. A small sheet of basalt extends downslope 60-90 m: giving an estimated volume of less than 50 000 m3. Based on flow morphology, this is probably 150 to 200 kyr.

A few magmas had just enough energy and mass to get to the surface but not enough to do much of anything with their new-found freedom. Certainly some never reached the surface.

Tecolote melted - it is unique

Tecolote, the brown mounds on the right, appears to be just one more ordinary cinder cone when seen from the rim of Elegante Crater, 4 kilometers to the south west. (11/11)

Ordinary until you look more closely; this volcano is unique. The right-hand ridge has several parallel lines - faults. Three valleys cut through the southern cone wall and each has a lava flow that lacks airfall cinder. The cone appears to have melted inside after it had been built!

The east ridge crest sank more than 3 m into the ridge. On the east slope (right side) the scarps are lit by sunlight streaming parallel to the slope; more numerous scarps on the west are in shadow.

Dawn light accentuates the the three valleys in Tecolote’s south side. Most of the modification occurred in the enigmatic “Cinder Block,” that gray wedge in front of the higher, bomb-covered, cone wall. Tecolote is probably the most important volcano in Pinacate because nothing like it has been described.

Great Maar-Calderas

Mile-wide MacDougal Crater, topmost in that line on the second (elements) image, is one of Pinacate’s great maar-calderas, a destructional landform blasted into the desert by steam explosions. Pinacate is famous for its maar calderas because they are dry, deep, and easy to visit. Most others in the world are lakes - that’s what the word “maar” means.

Elegante, on the northeast drive, is the largest in the field; 1600 m across, 250 m deep, a third to a half of a cubic kilometer volume. A basalt flow contemporaneous with the eruption has an Ar age of 32 pm 6 Ka.

Cerro Colorado is best described as a tuff cone. It erupted into the East Side Drainage, a wanna-be water course of about 2 m per km gradient that marks the eastern boundary of the volcanic field. Unlike the desert sites of the other maar-calderas, this place on the edge of the field has no stack of older basalts to hold up vertical walls of a pit.